Here’s the situation:

- You’re an expert policy analyst, and a client has asked for your help.

- Your client has a problem, and they’re expecting you to have the skills and expertise to solve that problem for them.

- Your client wants your solution to the problem in the form of a policy memo because they don’t have time to read anything longer

Where do you begin?

You might think the first step should be to read everything you can get your hands on. Or you might be more inclined to look for publicly available data sets and brainstorm calculations you could perform. It’s tempting to think that once you’ve learned as much as you can about a topic, you’ll be able to come up with a solution to your client’s problem. A better way to begin is to ask yourself what the client doesn’t yet know. More specifically, what is it they need to know to fulfill their mission or achieve their goals?

What next?

To start, there are likely three questions your client could be struggling to answer:

- What is happening?

- What is working?

- What should be done next?

Your client could be struggling to answer one of these questions or all three. For example, imagine your client is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to reduce the amount of meat consumed by Americans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and decrease the harmful effects of climate change. What don’t they know that they need to know to fulfill their mission?

- What is happening?

- How much meat is consumed annually in the United States? How many metric tons of greenhouse gas does the production and transportation of meat emit on an annual basis?

- What is working?

- What efforts have already been undertaken to reduce meat consumption, and how effective have those efforts been?

- What should be done next?

- What policy options could be implemented to help reduce the amount of meat that is consumed and thereby reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the United States?

Once you know what unknowns are keeping your clients from fulfilling their missions or achieving their goals, you can be more selective in your research, data collection, and analysis to ensure you are being as efficient with your time as possible. After you know enough to answer your client’s questions, it’s time to move onto constructing your narratives based on your rigorous analysis.

Check out our post on mastering the three policy narratives below:

Using the four elements to frame your proposal

Instead of getting lost in an internet search or a regression analysis when tasked with solving a client’s problem, you’ve now determined what questions your client had and then set out to provide answers to those questions.

The next step is to determine which pieces of evidence you’ll need to make each type of policy answer as persuasive as possible. In public policy, we can divide evidence into four distinct types:

- Status: What is happening?

- Criteria: What should be happening?

- Interpretation: Why is it happening?

- Outlook: What will likely happen next?

A descriptive policy answer will require only a status because a descriptive policy answer does not result in a policy recommendation. That doesn’t mean, of course, that it isn’t a valuable undertaking to provide a client with a descriptive policy answer. Helping a client understand what is happening can be a hugely important contribution. Evaluative and prescriptive policy solutions, on the other hand, require you to include ALL four elements of a policy finding if you want to persuade your client to implement your policy recommendation.

Take a deeper dive on the four elements in the post below:

Anatomy of a policy memo

The memo is ubiquitous across a variety of public and private industries. Consequently, the memo can take many different forms. An opinion memo, for example, is a format meant to circulate among decision makers to collect their opinions on a given problem or solution. A decision memo, otherwise known as an action memo or memorandum, is often written for a much smaller audience and meant to compel them to action. Most federal entities use the decision memo format to move recommendations up and down the chain of command, each department with its own formatting requirements, such as this one from the Department of Homeland Security.

Given their prominence and importance in almost every industry a policy professional will find themselves, it’s important to highlight some similarities across the many different memo formats you will encounter beyond your studies.

Executive Summary

One primary distinction between business memos and the more formal memorandums of government services is that a business memo will often start with a summary of the four essentials; this is intentional as your audience often has less time to read the full document before they make a decision. Some federal entities, such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO), have adopted a similar approach, such as GAO’s use of “Fast Facts” in their reports.

In the executive summary, you will state your recommendation, starting with your main point first. Then briefly summarize your main findings as answers to your client’s questions. Essentially, you are explaining why you are recommending they take action. End the summary with a brief statement of what will happen if the client implements your recommendation.

Background and Methodology

Here you will provide context and any historical or technical information the reader may need to understand your findings and nothing more. Consider what your reader already knows. You may also need to briefly explain where your data comes from and how they were analyzed. Depending on your findings, you may not even need a background and methodology section.

Key Findings

In the key finding section, you will answer your client’s questions directly. You will also provide evidence (and the context surrounding the evidence), as well as your analysis of the evidence in support of your descriptive, evaluative, or prescriptive answer. You may also need to include information on any limitations associated with your findings and rebut alternative options, if necessary.

Your key findings should be written out in complete sentences with subjects and verbs. Depending on the scope of the memo, especially in the case where there are several different but related questions to answer, it may make sense to organize your findings by topic; in this case, make use of subheadings within your key findings, making sure to give each a clear name that will be intuitive to your reader.

Recommendation

Your recommendations should link the root causes of the requestor’s problem, which you should have identified in your key findings section, and include what needs to be done by whom. Your recommendations should be feasible, cost effective, and specific without being too narrow. It should be clear who is being asked to act—whether it is an individual, a team, or an entirely different unit—and what is being requested of them.

Conclusion

While not essential by any means, sometimes a conclusion will help further compel your audience to action by assessing the impact of your recommendation to the greater good as they understand it. Your conclusion should place your key findings in a broader context that reminds the reader of the issue’s importance. Why is it important that action be taken immediately? A good conclusion will weigh loss aversion against hope for the future as motivating factors.

Writing recommendations that matter

To be most effective, recommendations to improve operations or conduct further research should clearly identify feasible actions that need to be taken and provide the appropriate level of detail to facilitate implementation and subsequent follow up. Other considerations include:

Address your recommendation to a person or program so that it’s clear who’s responsible for ensuring the recommendation is implemented.

To be valuable to your client, your recommendations must

- explicitly connect to the description of the evidence

- evaluate between the cause of whatever barriers or challenges are holding the client back vs. the potential outcome you would expect to arise from the recommendation

- be feasible, cost-effective, and measurable

Focus on concisely presenting who should do what and why. Avoid phrasing that reintroduces the barriers or challenges you uncovered. That information should be presented in the key finding section.

If you’re making multiple recommendations, use a lead-in sentence like: “We are making four recommendations to improve program operations…” Your recommendations can then be placed into a numbered or bulleted list below the lead-in sentence.

Choose specific phrasing (e.g., explore vs. ensure and plan vs. implement require different actions).

Avoid being unnecessarily prescriptive. If you want to recommend that certain steps be taken, those steps could be introduced with “including . . .” or similar language. If, on the other hand, you want to recommend that your client determine their own course of action to meet your recommendation’s intent, you can introduce those steps with “such as . . .” or similar language.

Structuring paragraphs deductively

Being understood can often come at the expense of surprising our reader, but when precision and coherence are most important to your audience, you will want to be clear about your big idea from the start. Deductive structure is just a fancy name for the “topic, then comment” structure of academic and professional communication. Structuring a paragraph deductively simply means that the main point of the paragraph is presented in the first sentence. The remaining sentences in the paragraph should present the data, facts, and statistics—along with your analysis and reasoning—needed to prove the point you make in the first sentence.

The key findings section is a great place to apply this lesson, but it can be useful in background sections as well. For example, when talking about an issue with a long history of ineffective solutions, you may be tempted to list them all out in chronological order alongside their poor outcomes. However, this may overwhelm your reader, especially if they have limited power to implement a fix to every problem, so starting with a clear purpose will enable you to filter out results that are off-topic or otherwise irrelevant to the case you make.

For example, imagine you are exploring solutions to reduce the amount of veterans experiencing homelessness across the United States. It won’t make much sense to analyze every solution as there are many different causes to this notoriously difficult problem that fall within the purview of multiple federal, state, and local entities. However, if we want to look strictly at folks who have lost ownership of a home, it may make better sense to let your reader know from the start, examining the VA home benefit through the lens of the Great Recession and Covid-19 pandemic, for example. Or, maybe it makes more sense to talk about employment, as it is often a pathway to home ownership when it is stable and at a fair rate—then you may want to look at measures that help veterans get jobs, such as veterans’ preference programs like Feds Hire Vets.

For more on writing deductively, check out our guide below!

Improve clarity with stronger sentence cores

Once you’ve created a clear, deductive structure in each paragraph and resolved any issues with content (substantive edits), it’s time for some line editing. To some, line editing can be both tedious and monotonous, but it doesn’t have to be. Good editing is about understanding style—the Chicago Manual of Style being the preferred style of the University of Chicago—and how it affects certain elements of the text, such as capitalization (i.e. “drop styles”) and citations. The online version of the Chicago Manual of Style is available to all UChicago students free of charge on the library’s main page (right side).

As you begin to line edit, reading line-by-line, take the opportunity to recast any sentences that can cause ambiguity or be cumbersome to read. One lesson we love to preach to our writers is the use of strong sentence cores alongside active verbs. All this means is that sentences with subjects and verbs close to the beginning are generally easier to read than those with lots of modifiers between the two.

Check out our guide on on strong sentence cores using active language below!

Simple tools to make the writing process easier

Using chatbots to reduce existing text

While the Writing Workshop DOES NOT recommend the use of chatbots such as Chat GPT to generate text from scratch, they agree that some features offer a few quality of life improvements for smaller tasks such as paraphrasing and reducing existing text. To start, make sure you include good instructions—the more specific you make the task, the better the chatbot will perform.

- For example: I’m writing a public policy memo for my economics class and need to paraphrase a few sentences from a report. I don’t want you to add anything to the text I give you, just focus on summarizing the most important elements, specifically ____. I will provide my own citation; don’t start writing until I give you the text to paraphrase.

Notice the guardrails that have been attached to the prompt here. Guardrails are an essential piece of any prompt as they keep the chatbot focused and on-task. One benefit of dedicating time to these prompts is that even free versions of chatbots like Chat GPT will save your prompts for later use, making it easy to copy, paste, and edit them for different assignments.

Using your own writing, you can apply this same strategy to reduce large blocks of text to shorter passages. For example, you may have a section from a longer report or article that you’ve written that you would like to use as a key finding. In this case, you can alter the prompt to retain the essential information about ____ and clear the clutter. Keep in mind that you can further prompt chatbots like Chat GPT to be more extreme in their reductions (“Make it shorter and eliminate any text about ___”). Always make sure to check for any citations that may have been eliminated in this process, especially if you have used footnotes.

Using Expresso to analyze your own writing

Expresso is a powerful, free-to-use web app that does not retain or save any text you enter. It is also a great example of how simple tools like the open-source spaCy library can be used to great effect, free of charge. Expresso is much less intrusive than a chatbot; rather than altering or generating text, it looks for different features within the text and provides you with controls to highlight elements such as sentence types, parts of speech, and different lexical categories.

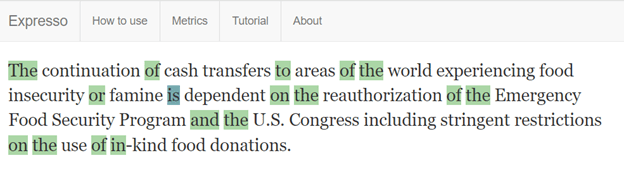

Expresso is a great tool for strengthening sentence cores while clearing the clutter. In the example below, taken from our post on sentence cores, I’ve selected “predicate depth” and “stop words” to reflect a verb detached from it’s subject along with some of the clutter it causes.

In the example above, we have both a weak verb and an unclear, abstract subject (“The continuation of . . .”). The amount of stop words (words that don’t carry meaning themselves) at the beginning tells us that there is likely an abstraction that will be hard for the reader to visualize because it is both inanimate and complex—”clustered nouns” is also a great metric for highlighting weak or complex subjects. The depth of the predicate (verb) and its type—stative in this case, which are often considered weak verbs—tell us that our time will better allocated to finding a clearer subject (US Congress) and stronger verb (transfer; restrict; reauthorize).

While you will spend a lot more time in revision compared to the ease of use that a chatbot provides, the value of the lessons you learn in the process and awareness of your own habits as a writer will be the reward for your time. Given the ongoing debates on the misuse of chatbots in professional and academic settings, it may also make sense to learn about some of the raw materials they are composed of. The Natural Language Toolkit and spaCy represent nearly two decades of advancements in the field of natural language processing and are essential to understanding how the complex “black boxes” built on top of them function.

Use a checklist as you edit

Our final piece of advice for you is to make writing a process. Whether you’re writing a policy memo for class or delivering aid to a few thousand folks in need, every process needs a checklist to ensure that no step has been skipped and all tasks critical to success have been completed. In the link below, we’ve provided a checklist for you to use as you complete your memo. As you discover what works best for you, feel free to borrow, alter, and amend any and all items we have provided.

Happy writing!